New York City has a housing problem. Currently, it has 1.8 million one- and two-person households, and only one million studios and one-bedroom apartments. The obvious solution seems to be to develop more small residential units.

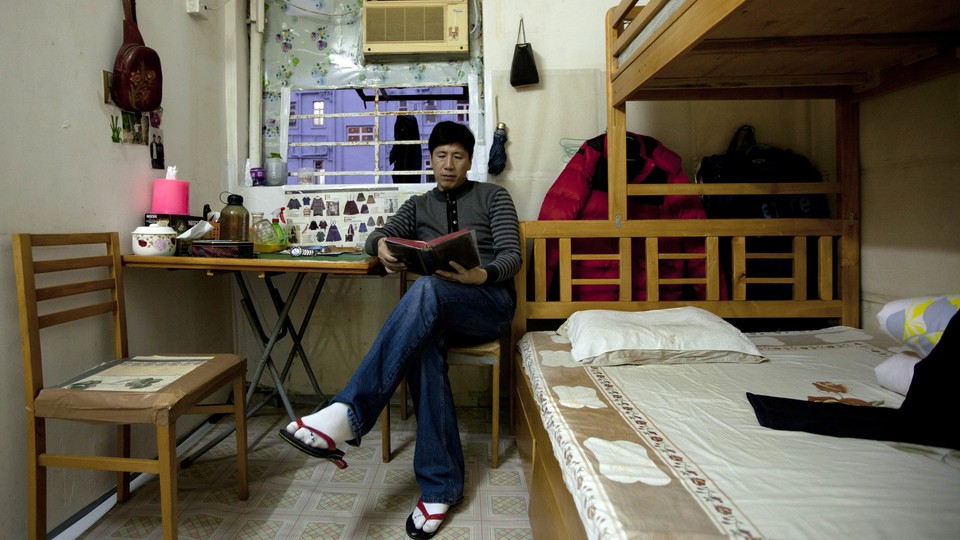

But how small is too small? Should we allow couples to move into a space the size of a suburban closet? Can a parent and child share a place as big as a hotel room?

In January, Bloomberg’s office announced the winner of its 2012 competition to design and build a residential tower of micro-units—apartments between 250 and 370 square feet—on a city-owned site at East 27th street in Manhattan. According to the Mayor’s press release, the winning proposal, by the Brooklyn-based firm nARCHITECTS , was chosen for its innovative layout and building design, with nearly 10 foot ceilings and Juliet balconies that give residents “substantial light and air.”

But as New York City’s “micro-apartment” project inches closer to reality, experts warn that micro-living may not be the urban panacea we’ve been waiting for. For some residents, the potential health risks and crowding challenges might outweigh the benefits of affordable housing. And while the Bloomberg administration hails the tiny spaces as a “milestone for new housing models,” critics question whether relaxing zoning rules and experimenting with micro-design on public land will effectively address New York’s apartment supply problem in the long run.

“Sure, these micro-apartments may be fantastic for young professionals in their 20's,” says Dak Kopec, director of design for human health at Boston Architectural College and author of Environmental Psychology for Design. “But they definitely can be unhealthy for older people , say in their 30’s and 40’s, who face different stress factors that can make tight living conditions a problem.”

Home is supposed to be a safe haven, and a resident with a demanding job may feel trapped in a claustrophobic apartment at night—forced to choose between the physical crowding of furniture and belongings in his unit, and social crowding, caused by other residents, in the building’s common spaces. Research, Kopec says, has shown that crowding-related stress can increase rates of domestic violence and substance abuse.

For all of us, daily life is a sequence of events, he explains. But most people don’t like adding extra steps to everyday tasks. Because micro-apartments are too small to hold basic furniture like a bed, table, and couch at the same time, residents must reconfigure their quarters throughout the day: folding down a Murphy bed, or hanging up a dining table on the wall. What might seem novel at the beginning ends up including a lot of little inconveniences, just to go to sleep or make breakfast before work. In this case, residents might eventually stop folding up their furniture every day and the space will start feeling even more constrained.

Susan Saegert, professor of environmental psychology at the CUNY Graduate Center and director of the Housing Environments Research Group, agrees that the micro-apartments will likely be a welcome choice for young New Yorkers who would probably otherwise share cramped space with friends. But she warns that tiny living conditions can be terrible for other residents—particularly if a couple or a parent and child squeeze into 300 square feet for the long term, no matter how well a unit is designed.

“I’ve studied children in crowded apartments and low-income housing a lot,” Saegert said, “and they can end up becoming withdrawn, and have trouble studying and concentrating.” In these situations, modern amenities—such as floor to ceiling windows, extra storage and a communal roof deck— won’t compensate for a fundamental lack of privacy in a child’s home every day.

She also doubts whether it’s a valid public goal to develop smaller units on city land. “In New York, property is just gold,” she points out. “Isn’t this something a developer could do in a [Brooklyn] neighborhood like DUMBO and make a lot of money?” By the same token, if micro-apartments are indeed the wave of the future, Saegert argues, they increase the “ground rent,” or dollar per square foot that a developer earns and comes to expect from his investment. So over time, New Yorkers may actually face more expensive housing, paying the same amount to rent a studio in the neighborhood where they used to be able to afford a one-bedroom. With the gradual erosion of zoning rules, the micro-apartment could very well become the unit of the future, the only viable choice for a large number of renters.

Beyond the economic impact of smaller spaces, our homes also serve an important role in communicating our values and goals, or what scientists call “identity claims.” We tend to feel happier and healthier when we can bring others to our space to telegraph who we are and what’s important to us.

“When we think about micro-living, we have a tendency to focus on functional things, like is there enough room for the fridge,” explained University of Texas psychology professor Samuel Gosling, who studies the connection between people and their possessions “But an apartment has to fill other psychological needs as well, such as self-expression and relaxation, that might not be as easily met in a highly cramped space.”

On the other hand, Eugenie L. Birch, professor of urban research and education and chair of the Graduate Group in City Planning at the University of Pennsylvania, says this certainly isn’t the first time we’ve had this debate over micro-living. New York has grappled with the public health costs of crowded living conditions and minimum apartment standards throughout its history.

“Over time, New York City developers conceived of many ways to address the need for affordable housing,” said Birch. “They built slums in the 19th century that reformers fought against. Other solutions have been boarding houses, missions, shelters, and what came to be known as single room occupancy units or SROs.”

While it might be stressful to live in crowded conditions, consider the alternative.

Rolf Pendall, director of the Urban Institute’s Metropolitan Housing and Communities Policy Center asks: Where would all these people be doing business and living without the density? Would they be commuting longer distances or earning less, and is living farther from economic opportunities “better” for them? In that context, Pendall says he welcomes micro-apartments as long as they fit within the larger housing ecology of the city, and don’t ultimately displace other types of units for families.

The problem is, there’s often a discrepancy between housing standards and actual housing conditions. Countless New Yorkers illegally share apartments, and current zoning rules can create poor living environments—dilapidated kitchens or dark, dingy rooms with a window that opens onto a brick wall. A worst case scenario would yield hundreds of thousands of micro-apartments and poor conditions.

For this project, while New York may be taking a step backwards in terms of square footage, Eric Bunge, a principle at nArchitects, (the firm that created the winning micro-apartment design), is adamant that the city is taking a big step forward in terms of actual living conditions.

“The city sees this initiative as one mechanism in a set of complex issues,” Bunge says. “Nobody is claiming that micro-apartments will be a silver bullet.”

By his calculus, the East 27th street building does address concerns of mental and physical well-being. For example, residents might be losing physical space, but they’re gaining access to a series of amenities, like a gym with floor-to-ceiling park views, a lobby with a public garden, and yes, a Juliet balcony. And for that, many city dwellers might happily trade away 75 square feet and a freestanding bed.